OFOs: Interruptions and the New Natural Gas Order

Remember the early days of deregulation, when you could buy gas and actually receive it – even on the coldest of days? Anyone in today’s natural gas business understands that unless you have the right natural gas supply using the right transportation service, the reliability of your gas supply may be keeping you up at night.

The reason? The number of Operational Flow Orders (OFOs) and interruptions of gas supplies have now extended from markets that were at the end of the literal pipeline, into a growing number of regions across the country. OFOs have also been increasing in frequency and are no longer confined to the coldest winter days, a “polar vortex,” or a monikered winter storm, but have expanded to include every winter month from November through March – and even into those shoulder months. In fact, it seems that any time temperatures don’t hover near the 20-year average, pipelines and utilities are announcing OFOs.

For those of you not familiar with an OFO – it is essentially a mandate from a utility or pipeline (i.e., the regulated entity) that results from a mismatch between the amount of gas being supplied to its system, and the demand required by the market it serves. Historically, this occurred only on extreme weather days.

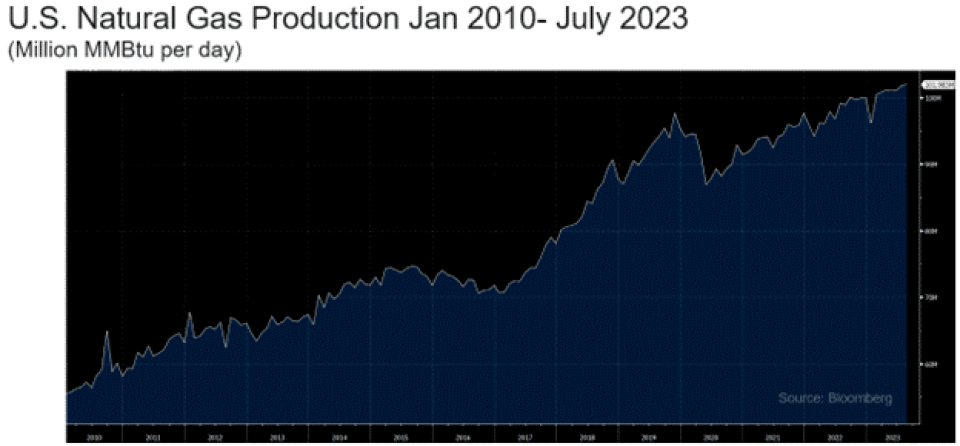

Over the past 13 years, natural gas production in the U.S. has nearly doubled from 55 Bcf/day in 2010 to nearly 102 Bcf/day today, as indicated in the chart below. American technology and production efficiencies were the starting points that allowed that growth to occur. But with such significant advancements, why would natural gas supplies to existing facilities prior to this growth be less reliable now?

I believe it has to do with a fundamental shift in the type of entities investing into and paying for infrastructure today, versus several decades ago. Deregulation of interstate pipelines via FERC Order 636 in the early 1990s made those entities simply transporters of gas without the opportunity – or responsibility – of buying the physical gas. The responsibility to ensure that enough gas was available was transferred down to the next regulated entity – local distribution companies (LDCs) – which picked up interstate pipeline capacity costs to make sure they could provide enough gas to meet demand in their markets.

As deregulation at the state level occurred in the first decade of the 21st century, LDCs decided that the cost to own space on an upstream pipeline to move a commodity they were no longer required to purchase was no longer prudent.

That’s when the gas purchase obligation shifted, for the first time, to an unregulated group of business classes that a) had no guarantee of a return like regulated utilities, and b) were allowed to use the regulated infrastructure to move their gas to any market that would keep them in business. Over the past 15 years, these two relatively new drivers of infrastructure investment were the producers of natural gas and the marketers that sell natural gas in deregulated markets.

This shift from regulated entities, which had defined regional markets that rarely overlapped and often owned excess pipeline capacity that could be recovered via rate increases approved by state regulatory commissions, were replaced by producers and marketers paying for pipeline capacity, who were just trying to get natural gas to a major gas hub or to the next customer.

This new endpoint for gas, which might be in a different part of the state or in a different region, is no longer bound by the restriction of where a single LDC system might go. Instead, there now exists an endless grid of possibilities that continues to expand as demand shifts from region to region, season to season, and even between fuel sources as renewables grow and coal continues to decline – all impacting where natural gas is needed.

So, while supply and infrastructure have grown significantly, the original flow direction, path, and ultimate destination of gas has also changed. The flexibility – and to some extent, reliability – of the old way, when regulated LDCs bought and sold most gas, now hinges on market pricing and pipeline grid options, which dictate the direction that gas flows on any given day.

This increased flexibility of where supply can go also comes with new challenges for end-use customers in the form of more frequent OFOs and growing price volatility.

Understanding the complexity of the pipeline grid, the bottlenecks, the flexibility of your LDC, and the quality of your supplier and contract is key to mitigating the growing risk of OFOs.

Let us help you navigate the clean energy transition.

By submitting your details in this form, you are agreeing to Trio's privacy policy. Trio is committed to protecting and respecting your privacy, and will only use your personal information to administer your account and to provide details on the products and services you requested.