FERC’s new perspective on natural gas infrastructure

By Jeff Bolyard

Pre-election political posturing has dominated media cycles for months leading up to the election on November 5. Since then, should you tune into a news broadcast, you’re not likely to hear much more than reactions to the election from both sides, filled with prognostications about what the new administration will mean for the future of our country.

Two and a half weeks before the election results were announced, buried deep within the news cycle, was something likely more telling about the future of energy in the U.S. than the volume of speculation that covered the headlines since. On October 17, without much fanfare, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approved three separate natural gas projects. What’s different about these approvals is that with three Democrats and two Republicans making up the current Commission, most natural gas projects end up with split votes. On this date, however, the approvals were unanimous.

The three projects included the following:

- 1.07 Bcf/day expansion of the Cameron interstate pipeline to serve the Cameron LNG export terminal in Louisiana

- 300,000 Dth/day combined projects by TC Energy’s Northern Border Pipeline and Kinder Morgan’s Wyoming Interstate Co. (WIC) to move gas from the Bakken Shale to the Cheyenne Hub in Colorado

- 325,000 Dth/day compression only project by MountainWest Overthrust to take gas from the Rockies Express Pipeline west of Cheyenne to the Opal Hub

Noticeably missing from the approvals was any significant debate over the climate impacts of the projects, which had previously been a point of contention within FERC, primarily driven by Democratic Chairman Richard Glick and Commissioner Allison Clements. However, neither of them is on the commission any longer, having been replaced with three new commissioners nominated by the Biden administration. Could it be possible that FERC is starting to work together as the bipartisan agency it was intended to be all along?

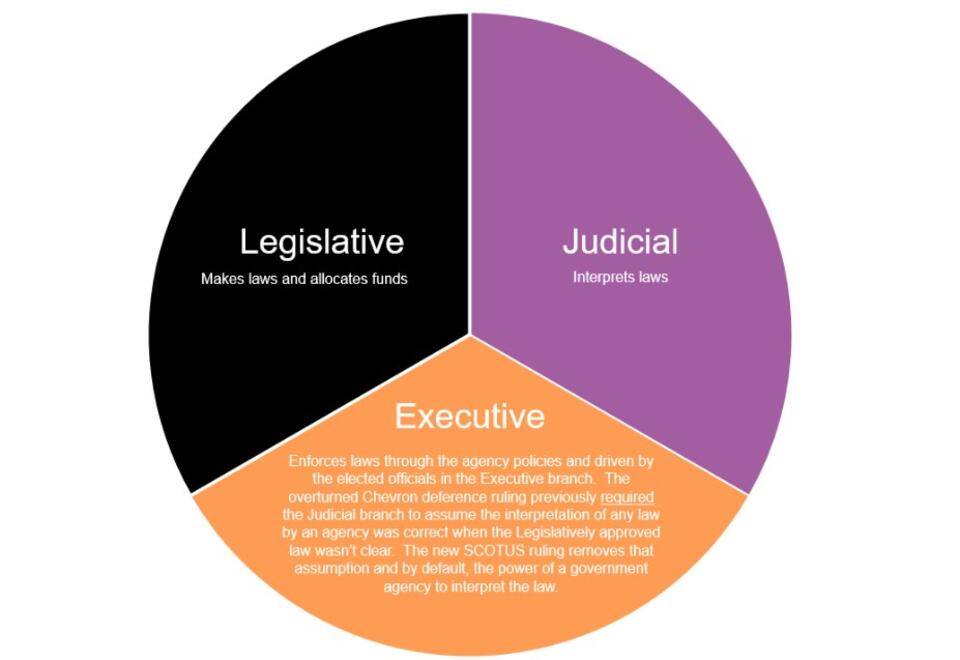

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision earlier this year, overturning the 1984 decision known as the Chevron Deference, may present a hurdle for FERC and other federal agencies when it comes to interpreting and administering laws. This far-reaching decision took the interpretation of law away from federal agencies and placed it back into the hands of the court, and courts are no longer required to uphold the agencies’ interpretation of the previous, ambiguous law.

Another clue to the meaning behind the unanimous approval may come from FERC Chairman Willie Phillips, who said the Commission “always follows” orders and precedents of the federal courts. FERC had recently been challenged by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, faulting the Commission’s inability to clearly explain and quantify how greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions were determined on a pipeline project that had been denied.

Even before the election, the way FERC and other agencies were operating had started to change. Whether you believe this shift in direction is good or bad is not the goal of this blog. Rather, it is to point out that changes are happening in the world of energy, and the runway of a consistent energy policy at the national level is still unclear.